Guest Blog by:

Connie Holubar, Director of Operations

Galveston National Laboratory

Anne Howard, MLS, a Medical Reference Librarian working at the Moody Medical Library at UTMB, recently gave a lecture about the growing practice of predatory publishing.

In her role with the library, Ms. Howard is often asked by faculty members to check out the legitimacy of a journal to determine whether or not it is real. “It’s not always easy to tell,” she said.

The problem of predatory publishing has been growing tremendously, taking advantage of the desperate need for faculty to “publish or perish” in order to be eligible for promotion. Many serious scientists nationwide have been duped into paying for publications they think are legit, but that may never see the light of day.

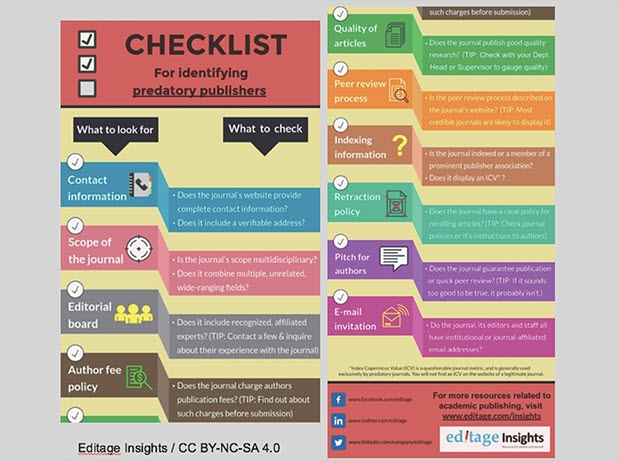

According to Ms. Howard, telltale signs that something may be fake or predatory include:

- Invitations to publish in an area outside your expertise

- Overly solicitous emails flattering you with your reputation as “renown” or “imminent”

- A rapid or “guaranteed” acceptance timeline, particularly in a supposedly peer-reviewed journal

- Grammatical mistakes in the email, possibly indicating that English is not the author’s first language

- A journal website that does not include archived past issues, a verifiable editorial board or a “real” street address

- Pressure within the solicitation to take advantage of the offer “now!”

While “pay to play” is a practice within even the most notable science journals, with fees commonly known as Article Processing Charges, or APCs, with a predatory offer, those fees may not be disclosed up front or the publishing process, including the peer-review process, is not well defined.

“Worst of all, many of the predatory publishers lock you into a contract that you can’t get out of. They have attorneys and will sue you if you cancel your payment. It is not uncommon for someone to be taken advantage of by a predatory publication but be on the hook for whatever fees were charged,” Ms. Howard said.

In addition, predatory conferences are also becoming a scam. Ms. Howard said that predatory conferences are now outnumbering official events, according to Times Higher Education. Offers to speak at or attend a conference, usually in an exotic location and for a fee, should be evaluated closely. If it sounds too good to be true, well, it probably is.

One place you can check for the legitimacy of publications is the Moody Medical Library website. The home page includes a list of Databases, and Ms. Howard notes that the Ulrich’s Online database is a great place to check for journal information.

In addition, she shared information about Stop Predatory Journals, an organization that maintains lists of predatory journals and publishers. They can be found at predatoryjournals.com and accept contributions to their lists, so if you receive an unusual “opportunity” to publish, you can send information about it to stop@predatoryjournals.com.